A new picture of dark matter

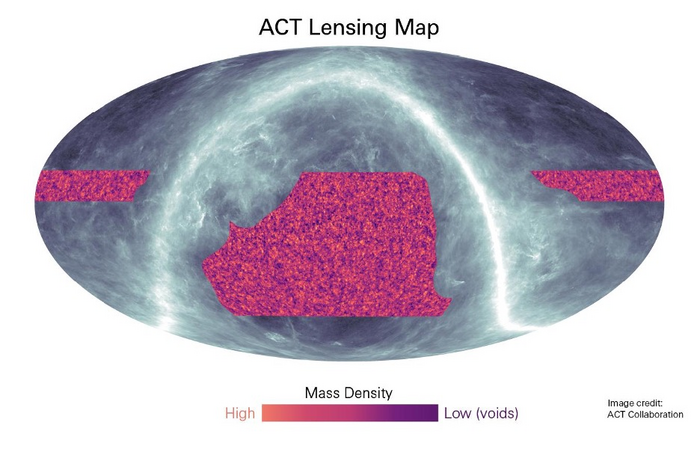

We can’t see it – but by observing its effects, we can still find out where it’s hiding. We’re talking about dark matter. Researchers at the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) have now used this principle to create a groundbreaking new image that shows the most detailed map of dark matter to date. It covers a quarter of the entire sky and extends deep into the cosmos. Moreover, it confirms – once again – Einstein’s theory of how massive structures grow and bend light over the universe’s lifetime of 13.8 billion years.

“We’ve mapped the invisible dark matter across the entire sky to the greatest distances, and we clearly see features of this invisible world that span hundreds of millions of light-years,” says Blake Sherwin, professor of cosmology at the University of Cambridge. “The distribution looks exactly as our theories predict.”

Although dark matter makes up 85 percent of the universe and influences its evolution, it is difficult to detect because it does not interact with light or other forms of electromagnetic radiation. As far as we know, dark matter interacts only with gravity.

To track it, the more than 160 people who built and collected data for the National Science Foundation’s Atacama Cosmological Telescope in the Chilean Andes observed light emitted after the universe was formed, the Big Bang, when the universe was only 380,000 years old. Cosmologists often refer to this diffuse light that fills our entire universe as the “baby picture of the universe,” but formally it is known as cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation.

The team is tracking how the gravitational pull of large, heavy structures, including dark matter, bends the CMB on its 14-billion-year journey to us, much as a magnifying glass bends light as it passes through its lens.

“We’ve created a new mass map by using the distortions in the light left over from the Big Bang,” says Mathew Madhavacheril, assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. “Remarkably, the measurements show that both the ‘lumpiness’ of the universe and the rate at which it is growing after 13.8 billion years of evolution are exactly what one would expect from our standard model of cosmology based on Einstein’s theory of gravity.”

Sherwin adds, “Our results also offer new insights into an ongoing debate that some call the ‘crisis of cosmology,'” explaining that this crisis stems from recent measurements that use a different background light emitted by stars in galaxies rather than the CMB. These have led to results suggesting that dark matter is not lumpy enough according to the Standard Model of cosmology, which has led to concerns that the model may be unusable. However, with the latest results from ACT, the team was able to determine exactly that the giant clumps seen in this image are just the right size.