Black hole winds are no longer what they used to be

In the early times of the universe, black holes in the centers of active galaxies grew much faster than today. Only in this way it can be explained that 500 to thousand million years after the big bang there were already such huge black holes. Today, however, things look different – the black holes at the centers are evolving in parallel with their host galaxies. When and why did this change occur?

That’s what a study led by three researchers from Italy’s National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) in Trieste has found, published in the journal Nature. The work is based on observations of 30 quasars – extremely bright, point-like sources in the nuclei of distant galaxies imaged with the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile. The host galaxies of these quasars were observed around cosmic dawn, when the universe was between 500 million and one billion years old.

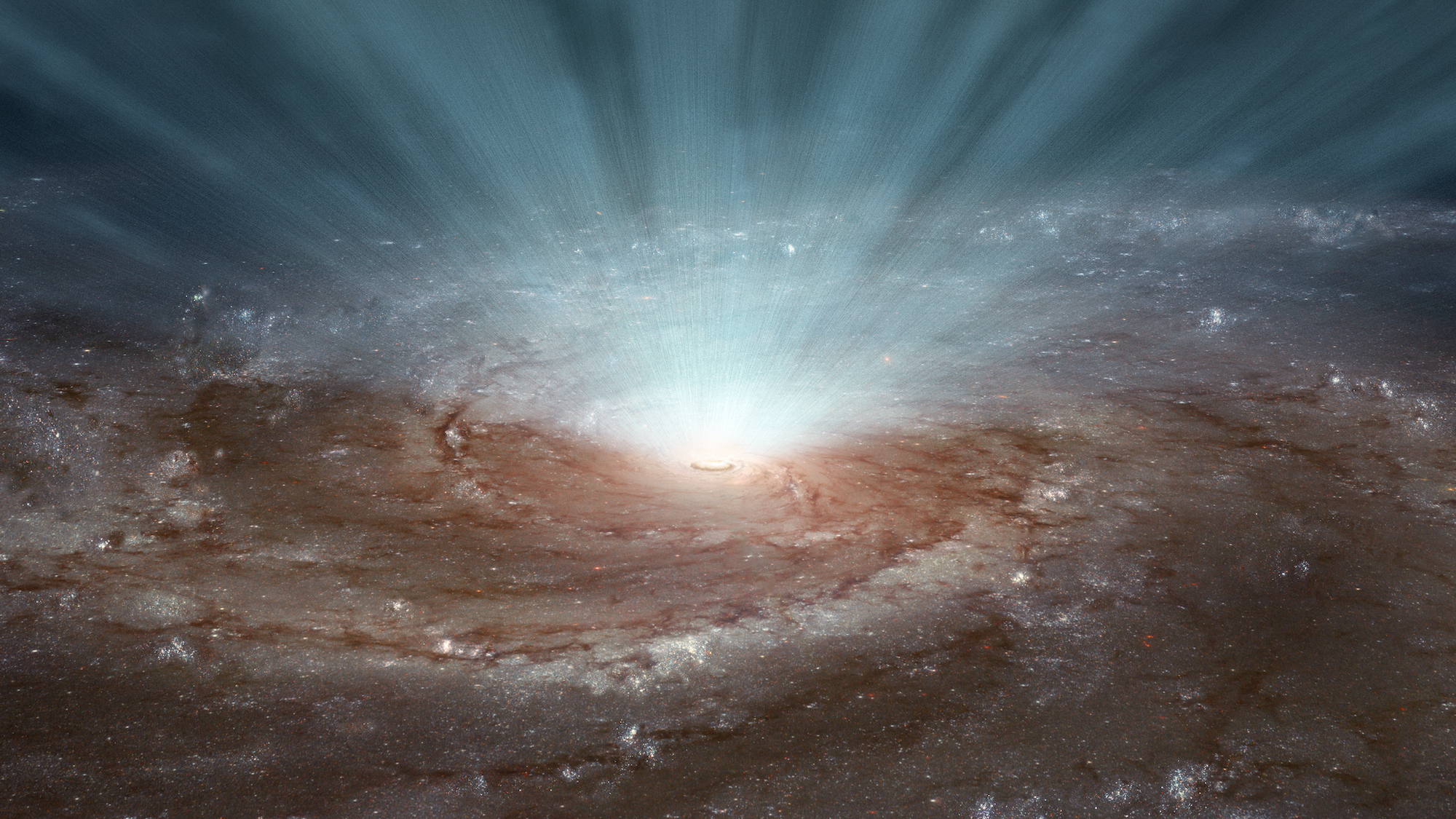

“For the first time, we have measured the fraction of quasars in the young universe that exhibit black hole winds,” said Manuela Bischetti, INAF researcher in Trieste and lead author of the study. These winds consist of hard radiation and streams of ionized particles. “In contrast to what we observe in the universe closer to us, we discovered that black hole winds are very abundant in the young universe, have high velocities of up to 17 percent of the speed of light, and inject large amounts of energy into their host galaxy.” About half of the observed quasars exhibited black hole winds, which are also 20 times stronger than the winds in quasars in the nearer cosmos.

The black holes have apparently made life difficult for themselves. Sooner or later, the energy introduced by the winds stopped the further accretion of matter into the black hole, slowing its growth and initiating a phase of co-evolution with the host galaxy.