More life at the first stars?

The very first stars consisted only of hydrogen and helium – there were no other elements in the still young cosmos. When they died in gigantic explosions, they released what had accumulated in them: heavier elements, which were needed so that planets could form. The more heavy elements (cosmologists call them “metals,” although chemically they aren’t necessarily), the more planets can form, the better chance life has, right? Not quite. Whether life has a chance depends on more than just the composition of a celestial body. In fact, planets located in the habitable zones of metal-poor stars may be the best targets for finding potential life, notes a new paper in Nature Communications.

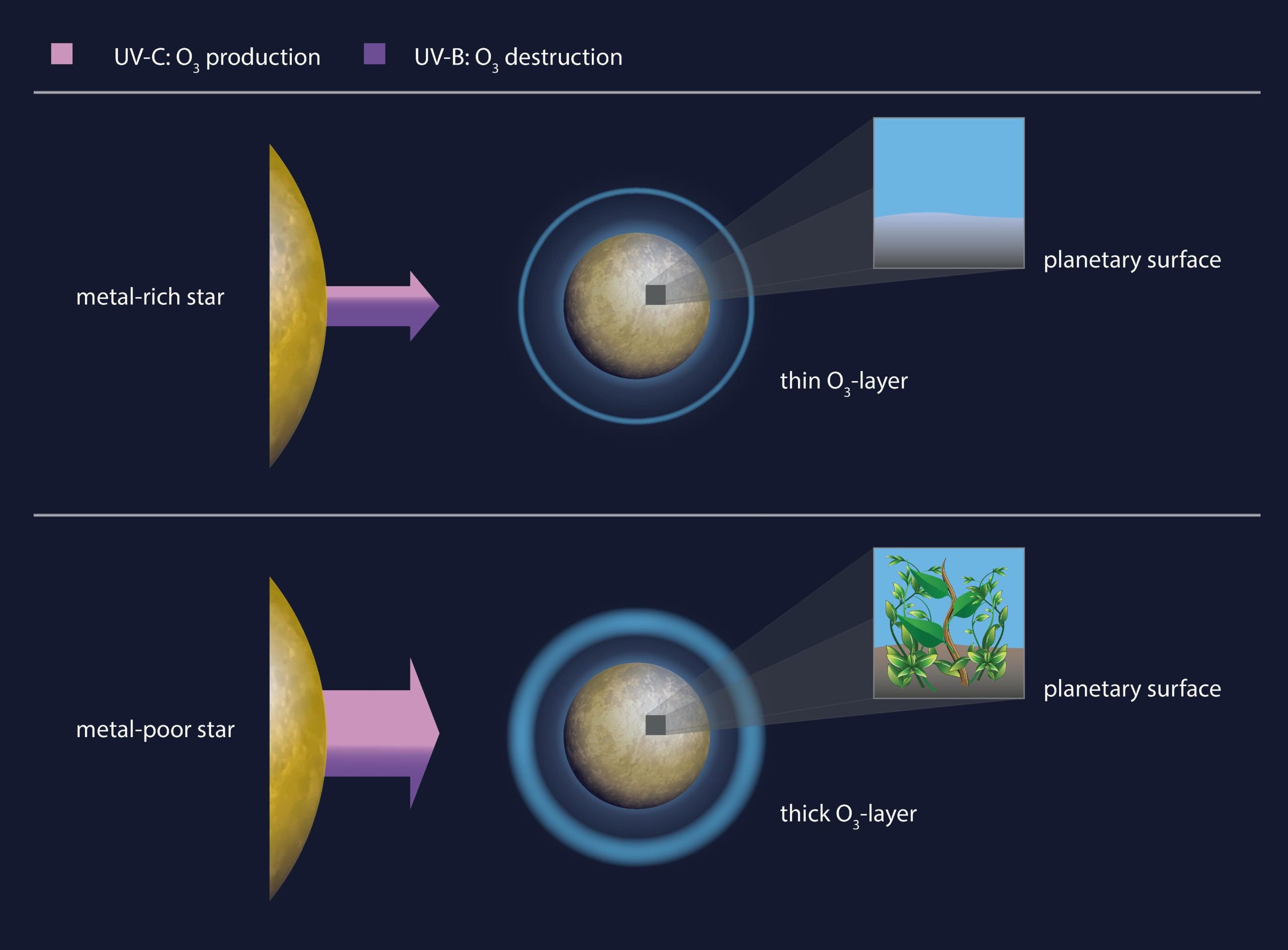

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which can damage the genetic material of living things, is to blame. Atmospheric oxygen and ozone protect Earth’s biosphere from harmful UV radiation from the sun, but the amount of UV emitted varies from star to star. It is known that low levels of stellar UV radiation result in low levels of ozone on the planet, and thus less UV protection. However, the influence of stellar metallicity, the abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, on planetary UV protection and habitability is unclear.

Anna Shapiro and colleagues now modeled the atmospheres of hypothetical Earth-like planets hosted by stars with different metallicities and found that planets around metal-poor stars have stronger UV protection, which could have implications for possible life. Although metal-rich stars emit much less UV radiation than metal-poor stars, the surface of planets associated with them is exposed to more intense UV radiation. The authors suggest that planets orbiting metal-rich stars are less suitable for life, even though they receive relatively little UV radiation. A surprising result!