Watching a planet grow

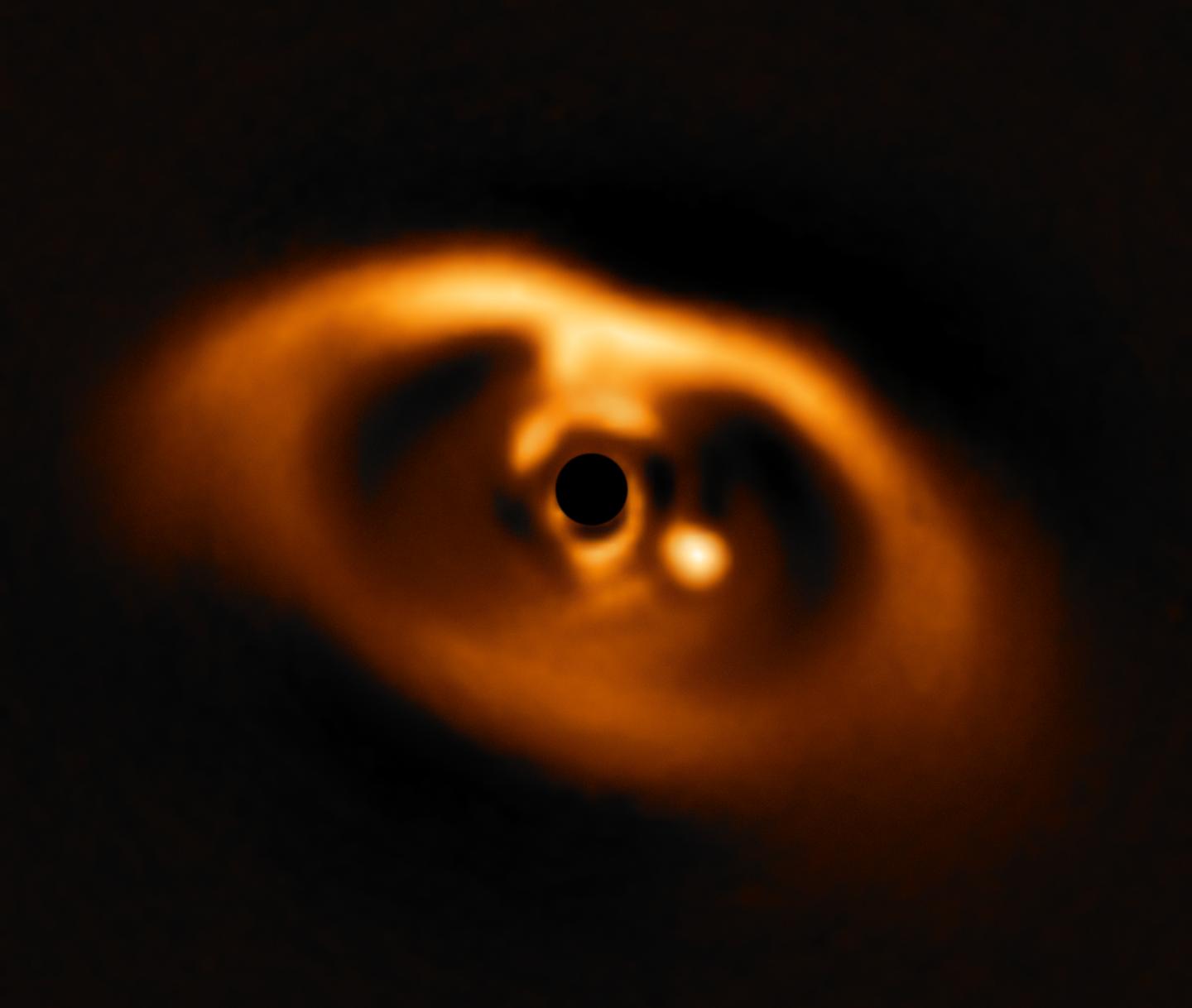

Astronomers usually detect exoplanets based on irregularities in the glow of the parent star. Although more than 4,000 exoplanets have been cataloged to date, only 15 have been imaged directly by telescopes. Even in their best photos, the planets are just dots, simply because they are so far away and quite small. A new technique from the Hubble team is now expected to help image planets directly. The researchers have used it to catch a rare glimpse of a Jupiter-sized planet, still forming, that feeds on material surrounding a young star. They report it in the Astronomical Journal.

“We just don’t know very much about how giant planets grow,” says Brendan Bowler of the University of Texas at Austin. “This planetary system gives us the first opportunity to observe how material falls onto a planet. Our results open up a new area for this research.”

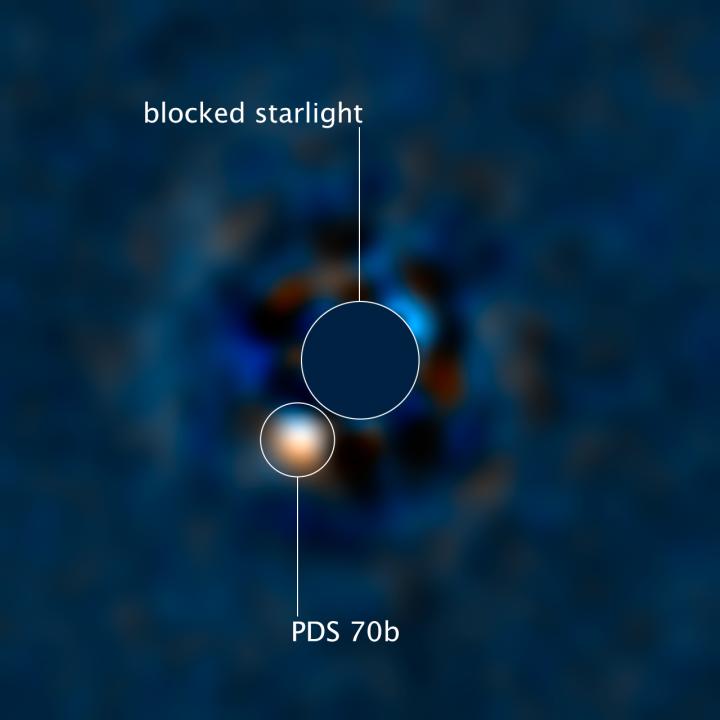

The giant exoplanet, designated PDS 70b, orbits the orange dwarf star PDS 70, which is already known to have two forming planets within a giant disk of dust and gas. The system is located 370 light-years from Earth in the constellation Centaurus.

“This system is so exciting because we can observe the formation of a planet,” says Yifan Zhou, also of the University of Texas at Austin. “This is the youngest planet Hubble has ever imaged directly.”

At a youthful five million years old, the planet is still gathering material and forming mass. Hubble’s sensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) light provides a unique view of radiation from extremely hot gas falling on the planet.

“Hubble’s observations have allowed us to estimate how quickly the planet is gaining mass,” Zhou added.

The UV observations, which add to the body of research on this planet, allowed the team to directly measure the planet’s mass gain rate for the first time. The remote world has already grown to five times the mass of Jupiter over a period of about five million years. In the meantime, however, the accretion rate has shrunk to the point that, if the rate remains the same, the planet will increase by only about one-hundredth of a Jupiter’s mass in another million years.

Zhou and Bowler emphasize, however, that these observations are a snapshot. More data are needed to determine with certainty whether the rate at which the planet is gaining mass is increasing or decreasing. “Our measurements suggest that the planet is at the end of its formation process.”

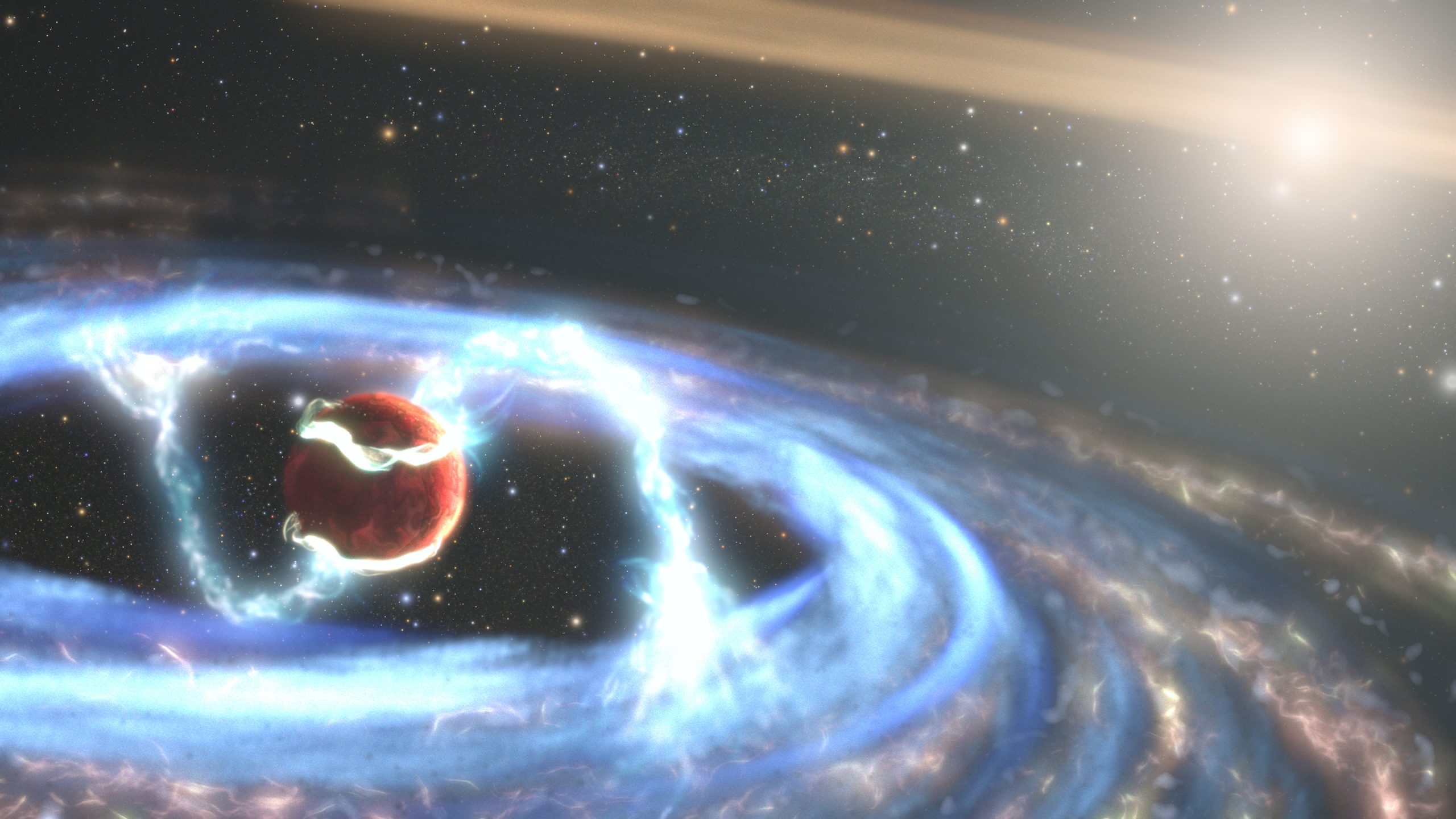

The youthful PDS 70 system is filled with a primordial disk of gas and dust that provides the fuel for planetary growth throughout the system. The planet PDS 70b is surrounded by its own gas and dust disk, which siphons material from the much larger circumstellar disk. The researchers suspect that magnetic field lines extend from the circumstellar disk into the exoplanet’s atmosphere, funneling material onto the planet’s surface.

A particular challenge for the team was blocking out the bright parent star. PDS 70b orbits the planet at about the same distance as Uranus orbits the Sun. But its star is more than 3,000 times brighter than the planet at UV wavelengths.