What does the interior of Neptune or Uranus look like?

Exploring the interior of icy giant planets is not an easy task. Without more advanced technology, we won’t be able to use probes to make measurements on site, so researchers must rely on models. These models are based on what scientists know about the substances that make up these ice giants such as Neptune and Uranus.

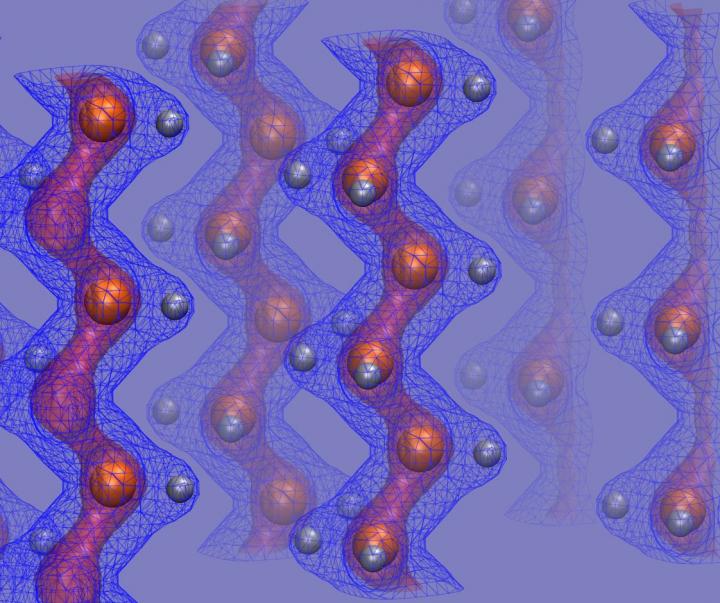

However, we can’t rule out that these models might contain errors. For example, it was previously assumed that carbon always took the form of diamond under very high pressures. Carbon and hydrogen are among the most abundant elements in the universe and make up a large portion of Neptune and Uranus, for example, in the form of methane. The deeper one goes down toward the center of either of these planets, the more extreme the conditions become. Initially, more complex structures of carbon and hydrogen are formed and then, at the very center, there is a solid core.

But not necessarily made of diamond, as determined in a laboratory experiment by an international team led by two researchers, Nicholas Hartley and Dominik Kraus, from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf (HZDR, Helmholtz Research Center in Dresden-Rossendorf). To do this, the researchers used polystyrene and polyethylene, whose chemistry is similar to that of the hydrocarbon in the interior of these planets. At the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in the USA, the scientists exposed samples to conditions like those that might exist some ten-thousand kilometers below the surface of Neptune and Uranus. There, the pressure is two million times greater than at the surface of the Earth.

According to previous assumptions, all the crystalline structures in both the polystyrene and in the polyethylene should have broken apart. In fact, however, for the polyethylene, the researchers observed stable compounds of carbon and hydrogen even at very high pressures. “We were very surprised by this result,” says Hartley according to the press release published by HZDR. “We did not expect the different initial state to make such a big difference at such extreme conditions. It’s only recently, with the development of brighter X-ray sources, that we’re able to study these materials. We were the first to think that it might be possible – and it was.”

During the experiments, the researchers were able to identify first results: “We were very excited because, as hoped, polystyrene formed diamond-like structures of carbon. For polyethylene, however, we saw no diamonds for the conditions reached in this experiment. Instead, there was a new structure that we could not explain at first,” Hartley says.

What is interesting in this discovery is that models for Uranus and Neptune previously assumed that the unusual magnetic fields of these planets were caused by free, metallic hydrogen. Now, however, it appears that there is less free hydrogen than previously assumed. So, the magnetic fields must have a different origin. Next, the researchers want to add oxygen to their experimental mixture, in order to better simulate the chemistry in the interior of the planets.