Big baby stars grow the same way as small baby stars

The protostellar object, G353.273+0.641, which is located 5500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Scorpio, is still a baby. It ignited only around 3000 years ago; astronomically, that is an extremely short amount of time. Nevertheless, G353 is already ten-times heavier than the Sun, and it’s still growing.

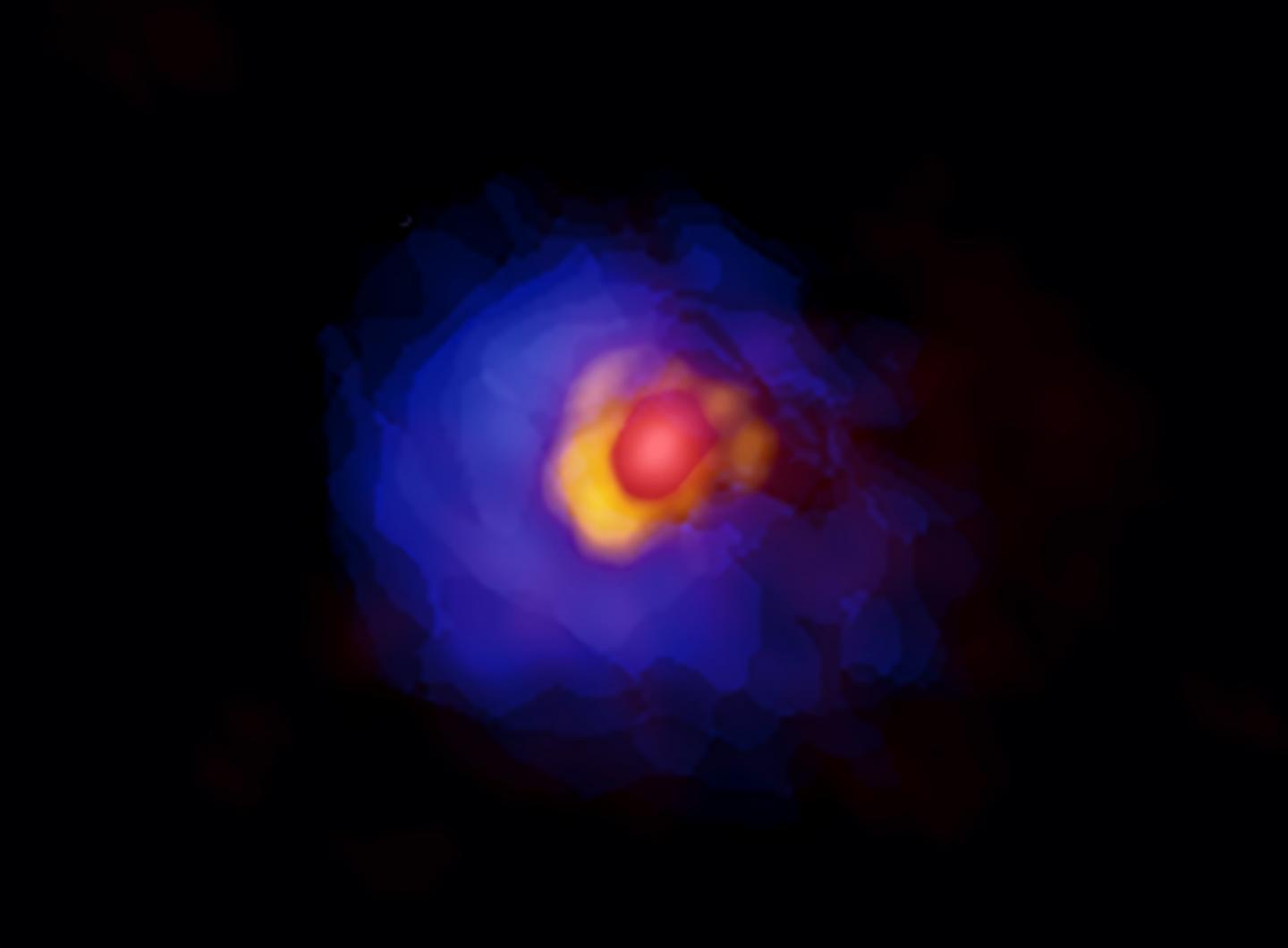

For the first time, researchers were able to catch a direct glance from above of such a massive protostar and its surroundings using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). In this way, they were able to determine that apparently size doesn’t matter. G353, in any case, acts no different than other lighter baby stars. As a protostar, it is surrounded by a dust disk, the protoplanetary disk, which is, in turn, fed by a gas cloud that surrounds the entire system.

With G353, the dust disk extends to a distance that corresponds to eight-times the orbit of the last planet in the Solar System, Neptune. That sounds impressive, but in comparison with other massive stars, it is still relatively small; in fact, it is the smallest disk discovered so far around a star of that size. In the ALMA images, it can also be seen that the gas cloud extends three-times deeper into space.

“We also measured the velocity at which the material is moving out of the outer cloud into the disk,” explains Kazuhito Motogi from the University of Yamaguchi, who led the study. “That allows us to calculate the age of the baby star. It is only 3000 years old. Thus, we are currently watching live the earliest phases of the birth of a giant star.”

Interestingly, the disk is not symmetrical. In the radio telescope’s images, its southeastern side appears brighter than the other parts. Astronomers had also never before seen a non-symmetrical dust disk around a massive protostar. The disk is probably unstable and will split off accordingly. Similar processes are also known from smaller stars. The separated pieces might even later form into additional stars.

“Earlier studies have found evidence that stellar formation differs for stars of different masses,” says Motogi. “Our new observations, however, point to commonalities.”