In the early universe, a hydrogen diet made black holes fat

Only a billion years after the big bang, there were already galaxies whose centers harbored supermassive black holes several billion times the mass of our Sun. Astronomers know this from observations of far distant quasars and active galaxies. But how were the black holes able to grow so large so quickly? The problem seemed even more complicated, because earlier observations with ALMA, the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array, had shown a lot of dust and gas in these early galaxies, which promoted rapid star formation. However, if a lot of stars were created, there would have been little left over to feed a black hole.

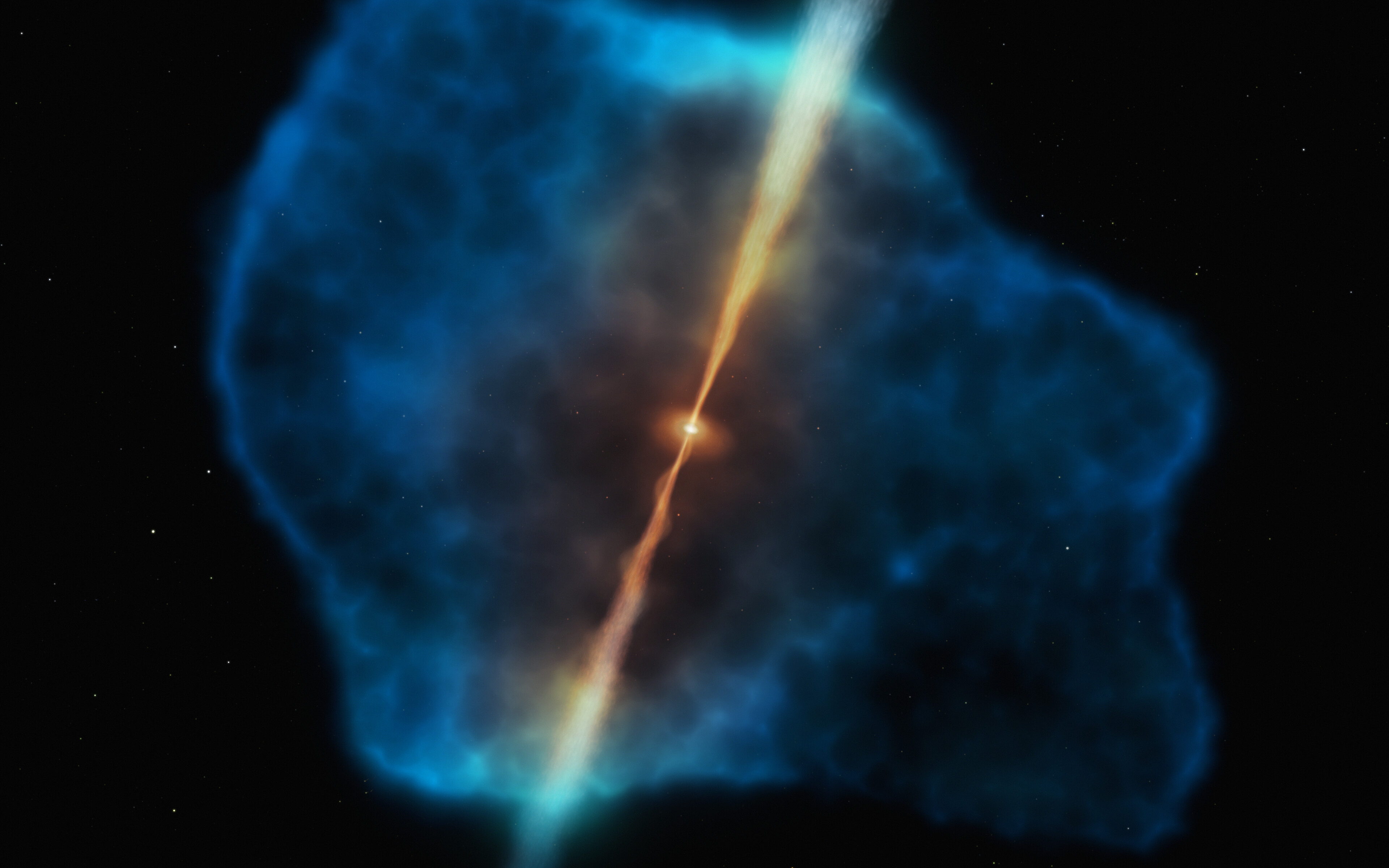

The solution: the young giants were fed from huge reserves of cold hydrogen gas. This finding was discovered by astronomers using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope.

“We are now able to demonstrate, for the first time, that primordial galaxies do have enough food in their environments to sustain both the growth of supermassive black holes and vigorous star formation,” says Emanuele Paolo Farina from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, who is the lead author of the research published today in The Astrophysical Journal. “This adds a fundamental piece to the puzzle that astronomers are building to picture how cosmic structures formed more than 12 billion years ago.”

“The presence of these early monsters, with masses several billion times the mass of our sun, is a big mystery,” says Farina, who also conducts research at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching bei München, Germany. To solve the mystery, Farina and his colleagues used the MUSE instrument on the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in the Chilean Atacama desert in order to study 31 quasars that are about 870 million years old.

In their research, the astronomers discovered that 12 quasars are surrounded by huge reservoirs of gas: halos made from cool, dense hydrogen gas extending more than 100,000 light-years out from the central black holes and having a mass greater than a billion times the mass of our Sun. The team also determined that these gas halos were tightly connected to the galaxies, making them the perfect source of material for supporting both the growth of supermassive black holes and also rapid star formation.