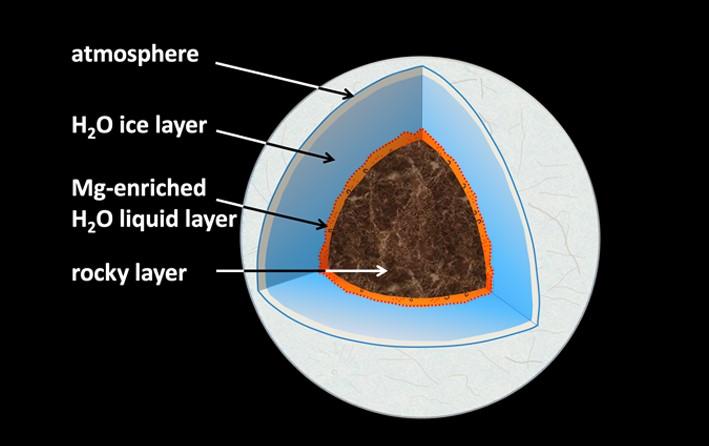

Water oceans in the crust of icy planets

A pressure 200,000 to 400,000 times that of Earth’s atmosphere, plus temperatures around 1500 Kelvin – these sound like uncomfortable conditions. They prevail where, in water-ice planets of the size of Neptune, the ice merges into the rocky core. Does liquid water exist under these conditions, and if so, how does it interact with the planet’s rocky seafloor? New experiments show that on water-ice planets between the size of our Earth and up to six times that size, water selectively leaches magnesium from typical rock minerals.

An international team of researchers led by Taehyun Kim of Yonsei University in Seoul, Korea, conducted a series of challenging experiments at both PETRA III (Hamburg, Germany) and the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, USA) that show how water at pressures between 20 and 40 gigapascals (GPa) strongly leaches magnesium oxide (MgO) from certain minerals, namely ferropericlase (Mg,Fe)O and olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4. To do this, the researchers placed beads of ferropericlase or olivine powder along with water in a tiny sample chamber drilled into a metal foil and pressurized them using a diamond anvil cell (DAC). They also heated the samples by shining an infrared laser through the diamond anvils.

They then observed the transformation and decay of minerals through reaction with water. Among other things, there was a decrease in the diffraction signal of the parent minerals and the appearance of new solid phases, including brucite (magnesium hydroxide). Sergio Speziale of the GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences explains, “This showed the onset of chemical reactions and the dissolution of the magnesium oxide component of both ferropericlase and olivine. The dissolution was strongest in a specific pressure-temperature range between 20 to 40 gigapascals and 1250 to 2000 Kelvin.” The details of the reaction process and the resulting chemical segregation of MgO from the residual phases were confirmed by thorough scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray spectroscopy of the obtained samples. The result is quite startling: “At these extreme pressures and temperatures, the solubility of magnesium oxide in water reaches values similar to those of salt at ambient conditions,” Speziale explains.

The scientists conclude that the intense dissolution of MgO at the interface between the water layer and the underlying rocky mantle could produce chemical gradients in water-rich sub-Neptunian exoplanets of appropriate size and composition, such as TRAPPIST-1f, during the early hot phases of the planet’s history. These gradients, which are a prerequisite for the later evolution of life, could be preserved at the planetary seafloor beyond the long cooling period. Traces of initial interactions between water and rocky material during planetary accretion would thus be preserved for billions of years, even for large icy planets the size of Uranus.