Even on smaller icy moons, the chances for life on the ocean floor are good

The fact that astrobiologists have such high hopes for icy moons like Enceladus or Europa is not only due to the oceans they have been able to detect under their ice crusts, but also to the fact that they are geologically active worlds. The culprits are the giant parent planets Saturn and Jupiter, respectively, which really knead the moons with their gravitational force. This creates heat, which keeps the water in their hidden oceans liquid and relatively warm. The water in turn dissolves from the underlying rock layers what potential life could need. Energy is also released in the process – a second, indispensable prerequisite for life.

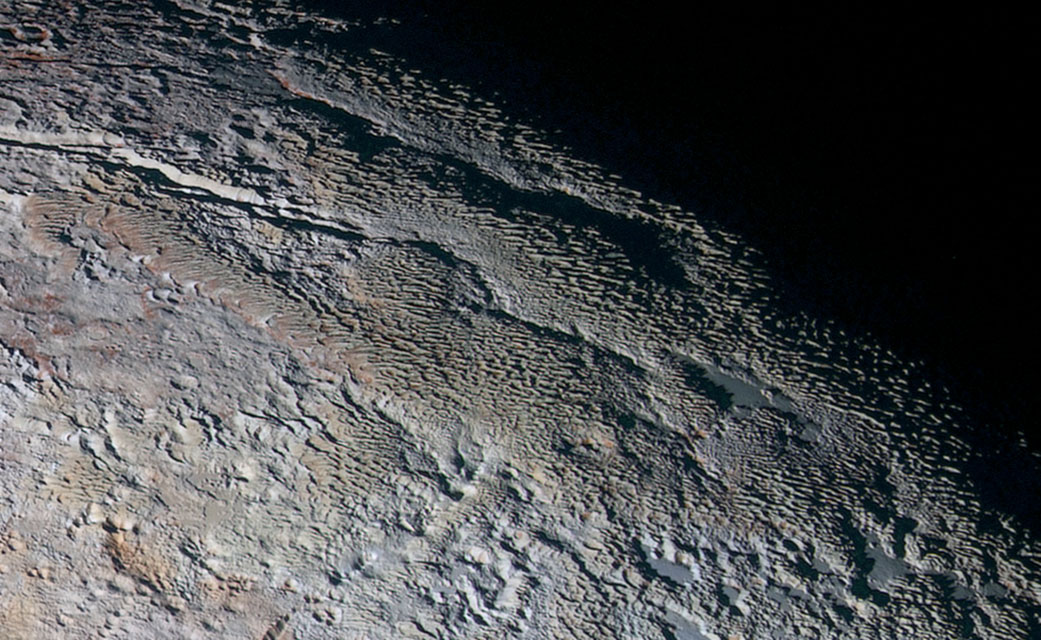

But what about worlds that lack such a vigorous massage – such as smaller moons of Saturn and Uranus or transneptunian objects like Pluto? It is true that water could also occur there in a liquid state – if enough salts are dissolved in it, the melting temperature of water drops. However, science previously assumed that at -20 °C water temperature the process stops, where the water dissolves the underlying rock. So no energy and no “food” at the bottom of Pluto’s ocean?

That appears to be a misconception, as now shown by an international team of researchers in Nature Astronomy. To do this, the researchers experimentally determined the rate and mechanism of dissolution of the mineral olivine in alkaline solutions at -20 °C, 4 °C and 22 °C for up to 442 days. The temperature range chosen corresponds to temperatures that can be reached in medium to large icy worlds from radiogenic sources alone, i.e., when there is no additional heat from tidal friction. Most icy worlds with diameters greater than 400 to 500 kilometers exceed this range, at least during the initial heating phase of their cores. The reactions studied are consistent with those previously determined from studies of Enceladus’ geyser plumes. The result is clear: “We find that chemical transformation processes are still effective at temperatures as low as -20 °C. The presence of an unfrozen water film allows olivine to still dissolve in alkaline solutions that are already partially frozen.” The scientists also conclude “that the transformation is enhanced by the salts and ammonia present in icy worlds and therefore remains a geologically rapid process even at temperatures below freezing.”